Written and Compiled by Gail Phillips

January 2016

First Aircraft and Flights into Anchorage

The first airplane flight in Alaska occurred in Fairbanks in 1913 and air travel in Interior Alaska was blossoming in the early 1920s, but Anchorage was about to become Alaska’s aviation center. The first aircraft to fly in the Anchorage area was a Boeing seaplane which had been shipped to Anchorage in pieces, aboard an Alaska Steamship Company freighter. This plane, owned by an Anchorage World War I aviator named C.O. Hammertree, was reassembled and prepared for flight in April, 1922. The first flight occurred on a day Cook Inlet was free of ice – pilot Roy Troxell flew the seaplane a few hundred feet into the air, circled around the Inlet and crashed into the mud flats. He was not hurt, but Anchorage’s first plane was demolished.

Established as a “Railroad Town,” the business folks of Anchorage worked on various ways to grow their community and economy. When plans to establish Anchorage as a marine shipping center did not quickly materialize, they turned their attention to aviation, which was rapidly growing in Interior and Northwest Alaska.

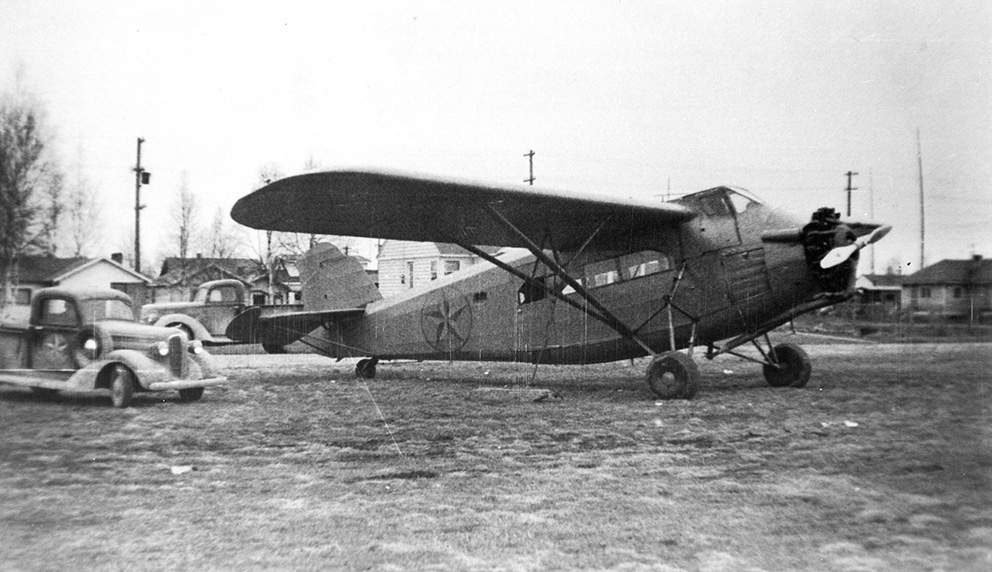

Anchorage had grown up around Ship Creek and by 1917 it extended as far south as Ninth Avenue. With only wilderness beyond Ninth Avenue, the time was right for the creation of an airstrip in Anchorage. Just past Ninth Avenue a piece of land had been set aside as a park in the original Anchorage township plat. Delaney Park was named for James Delaney, one of the first mayors of Anchorage. In 1923, under the guidance of Arthur W. Shonbeck, the entire town was organized to clear this strip of land of all trees, stumps and other hazards and this cleared land became a nine-hole golf course, a firebreak for the town and an airstrip for bush pilots.

By the summer of 1924, the Delaney Park Strip was open for business. On July 4, 1924, famed bush pilot Noel Wien performed aerial stunts in his Hisso Standard biplane that he named “Anchorage” to commemorate the opening of the Park Strip. Wien also made the first flight between Anchorage and Fairbanks in that year. With his brothers Ralph, Sig and Fritz, he founded Wien Air Alaska in 1927, the first airline in the State. Incidentally, Merrill Wien and his brother Richard, in a World War II Boeing Stearman biplane, took off from the Delaney Park Strip in Anchorage on July 6, 1999, to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the first flight from Anchorage to Fairbanks by their father.

Meanwhile, Arthur Shonbeck was determined to make aviation a serious business in Anchorage and in 1926 founded Anchorage Air Transport Inc, Anchorage’s first airline. Shonbeck hired a pilot from “the Lower 48” named Richard Hyde Merrill as the company’s first pilot. The new company flew freight and passengers to bush villages in the region. Merrill only flew for a couple of years, but during those years he is credited with being the first pilot to fly across the Gulf of Alaska, the first pilot to fly a commercial flight westward from Juneau and the first pilot to fly into the Kuskokwim River region directly from Anchorage. He later pioneered a shorter route to the lower Kuskokwim area through a pass in the Alaska Range. Named after him, that pass is now known as Merrill Pass. On September 16, 1929 Merrill disappeared on a flight to the NYAC Mine. His plane has never been found.

Merrill Field

By 1929, Anchorage and the fledging aviation industry were growing and the City of Anchorage was extending to the South. The Delaney Park Strip could no longer be safely used as an active airstrip and there was an increasing demand to relocate the landing facility. The Territorial Legislature, realizing the necessity for landing fields and airports throughout the Territory, made liberal provisions to aid municipalities desiring to establish and maintain airports. With the Territory bearing the major burden of the cost of construction and maintenance, municipalities, including Anchorage, were able to build or relocate airfields at little cost to themselves. After a petition by the citizens of Anchorage, resolutions by Mayor Delaney, the City of Anchorage and the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce and a promise of a matching grant from the Municipality, permission was granted by the federal Lands Office in Washington D.C., to develop an airport outside the city limits of Anchorage, to be known as Aviation Field. The Territorial Road Commission was charged with overseeing the operation of the new facility. When the new field became available for use in August 1929, Anchorage became the leader in air traffic operations in Alaska.

The following year the Anchorage Women’s Club petitioned to rename Aviation Field as Merrill Field, in honor of pilot Russ Merrill. The Road Commission granted the name change contingent upon approval by the Municipality of Anchorage. On April 2, 1930 Merrill Field received its official name and within a year, the city council had erected a steel tower with a rotating beacon adjacent to the runway.

The Anchorage-based aviation community was quick to move to the new facility and Merrill Field soon became the prominent airfield in the area. By the summer of 1931, all aircraft operators were advised to discontinue their use of the Park Strip. Merrill Field was the aviation facility for Anchorage. It became the busiest aviation center within Alaska and one of the busiest aviation facilities in the world.

Merrill Field was a first-rate aviation facility with two runways, a north-south and an eastward runway. It had an adjoining strip to accommodate ski-equipped aircraft during the winter season. Lighting was added to ensure safe night-time traffic and flight made during inclement weather.

Aviation continued to grow and by 1935, six airlines were operating off Merrill Field, which then was handling about 25% of all of Alaska’s air traffic. In 1939, the Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) installed and commissioned a Low Frequency Range Station at Merrill Field. Following its installation, Jack Jefford was the first pilot to fly the LFR Approach to Merrill Field. During the next several years, both runways at Merrill Field were increased in length to accommodate the increasingly larger aircraft using the facility.

Throughout the war years, Merrill Field operations continued to grow. In response to this increase in traffic, the old beacon tower was removed and a new wooden tower was commissioned.

In 1946, the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) began planning for future Alaska aviation patterns and the feasibility of a North Pacific air route. Once again, the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce stepped in to promote Anchorage as part of this new air route. They brought Anchorage’s case to Washington D.C., and told their story to President Truman.

On August 1, 1946, the CAB announced that three new air routes would converge in Anchorage. President Truman signed the order in June while the Anchorage delegation was still in Washington. Now that Anchorage was designated the junction point for international air routes, airlines immediately began requesting routes through Anchorage. Northwest Airlines received the rights for direct flights between Seattle and Anchorage, and from Anchorage to Minneapolis-St. Paul, Chicago and New York via Canada. Anchorage also became the North American terminal for the Great Circle Route to the Orient.

With all this activity, Merrill Field was rapidly growing and needed help from the CAA. In 1947, the city council requested, and the CAA built and manned, a control tower. By midsummer, Merrill Field had 125 based aircraft and approach lighting had been installed. It now had a paved 3,960-foot eastward runway and a 3,260-foot gravel north/south runway, The East/West runway was lighted and a localizer was installed that was used by both Merrill Field and the new military airbase at Elmendorf on the other side of Ship Creek.

Even with all these improvements, expansion at Merrill Field was limited. The City of Anchorage had reached Merrill’s boundaries and had begun to surround it. Merrill Field was unable to increase its facilities to accommodate the newer large transport planes. The safety concern of having the larger transport planes flying over the city making an approach into Merrill Field became another issue. Consequently, another delegation of Anchorage residents traveled to Washington on a mission to convince the federal government to construct an international airport in Anchorage.

Today, Merrill Field flourishes as a major general aviation facility. It has been classed as one of the largest flying schools in the United States. Its runways and navigational equipment are regularly upgraded and space around the air field is at a premium.

Military Aviation in Anchorage – Elmendorf Air Force Base

During the 1930s, rumors ran rampant concerning the establishment of military air bases in central Alaska. Both the Municipal City Council and the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce once again got involved in organizing a campaign to convince officials in Washington that Anchorage would be an ideal location for an air base. In the Spring of 1939, President Roosevelt withdrew 50,000 acres just north of Anchorage, between Knik Arm and the Chugach Mountains. Civilian settlement was restricted and the land was allocated for military bases. The War Department then appropriated $12.8 million to begin work on an air base four miles north of Anchorage. This became the Elmendorf/Richardson Base, with the Air Corps at Elmendorf and the infantry and support personnel at Richardson. Following World War II, the Base was formally separated in 1950 and became Elmendorf Air Force Base and Fort Richardson Army Base.

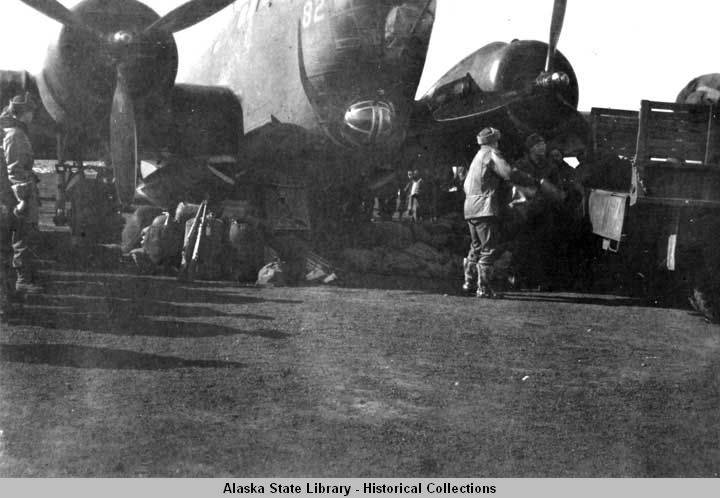

In April, 1940 the 4th Infantry arrived at Merrill Field with 774 enlisted men and 30 officers. Their function was to establish a tent city and begin construction on site at Fort Richardson. At about the same time the Eleventh Air Force contingent and the Alaska Defense Command also arrived at Merrill Field. Their job was to establish air operations in the newly selected wilderness site. They had to build the defense force from scratch, creating garrisons, airfields, communications and supply lines. This was a particularly difficult task since all supplies, including food, had to be shipped from Seattle. Their aircraft were based at Merrill Field while construction of the air base was taking place.

Construction began on the air field at Elmendorf on June 8, 1940 and was completed only nine months later in January of 1941. Several projects to lengthen and enlarge the air field have occurred over the years. Elmendorf became a focal point in the military’s air defense during the 1940s and World War II. The 18th Pursuit Squadron arrived in February 1941 and the 23rd Air Base Group was assigned shortly afterwards to provide base support. Elmendorf field played a vital role as the main air logistics center and staging area during the Aleutian Campaign and later air operations against the Kurile Islands.

Following World War II, Elmendorf assumed an increasing role in the defense of North America as the uncertain wartime relations between the United States and the Soviet Union deteriorated into the Cold War. The Eleventh Air Force was redesignated as the Alaskan Air Command (AAC) on December 18, 1945. The uncertain world situation in the late 1940s and early 1950s caused a major buildup of air defense forces in Alaska. This included an extensive aircraft control and warning radar system with sites located throughout Alaska’s interior and coastal regions, the White Alice Communications System and the Alaskan NORAD Regional Operations Control Center at Elmendorf, which served as the nerve center for air defense operations in Alaska. Elmendorf earned the motto “Top Cover for North America.” The Alaskan Air Command adopted this motto as its own in 1969.

A turning point in Elmendorf’s history occurred in 1970 with the arrival of the 43rd Tactical Fighter Squadron from MacDill AFB, Florida. The squadron gave the Alaskan Air Command an air-to-ground capability which was further enhanced with the activation of the 18th Tactical Fighter Squadron in 1977. The 1980s and 1990s brought a period of growth and modernization of Elmendorf AFB. Alaska’s air defense force was greatly enhanced with modern equipment aircraft and communications advancement.

Elmendorf Air Force Base is the largest Air Force installation in Alaska and home of the Headquarters, Alaskan Command (ALCOM), Alaskan NORAD Region (ANR), Eleventh Air Force (11th AF) and the 3rd Wing. In 2010, it was merged with Fort Richardson to become Joint Base Elmendorf/Richardson (JBER).

Because of the increased size and complexity of the 3rd Wing, the Air Force assigned a general officer as its commander in July 1993. Elmendorf AFB continues to grow in size and importance because of its strategic location and training facilities. The Wing now has responsibilities far beyond the vast borders of Alaska.

Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport

Soon after World War II, it became very evident that the airplane and aviation industry was here to stay in Alaska and Anchorage was rapidly becoming the transportation and economic hub of Alaska.

Recognizing the need for a larger, more modern airport in Anchorage, Congress, in 1948, approved an appropriation to build a new airport close to Anchorage. A site near Lake Hood was selected because it was away from the city’s main population areas and there was already a road in place between the city and Lake Hood. Construction on the new airport, which included an 8,400-foot East/West runway and a 5,000-foot North/South runway, began the next year. Construction of the first terminal for Anchorage International Airport began in 1952.

The Anchorage International Airport was opened for business in 1953. This airport is essential to all of Alaska with an estimated 90 percent of Alaska’s passenger traffic and 65 percent of its mail transported by Anchorage-based airlines.

During the mid 50s, the Europe to Asia “over the Pole” commercial traffic began routes through Anchorage and by 1960, Anchorage had established itself as the “Air Crossroads of the World.” At this time, seven international carriers used the Airport as a regular stop-over on routes between Europe, Asia and the East Coast of the U.S. Traffic continued to increase and with the advent of larger jets, it was soon apparent that the airport’s runways would have to be lengthened.

1959 brought great news to Alaska. On January 3, Alaska became the 49th State and the federal government officially transferred ownership of the Anchorage International Airport (AIA) to the new State of Alaska at an estimated value of $11,650,000.

In order to accommodate increased traffic and larger aircraft, the original East/West runway was extended to 10,600 feet and parking aprons were built to handle growing commercial jet traffic.

Then, in 1964 disaster struck with the Good Friday Earthquake, the largest quake in North America at that time with a magnitude of 9.2 on the Richter scale. Severe damage occurred at the airport, which included the collapse of the main control tower and partially-destroyed passenger terminal. In spite of runway damage, a damaged lighting system and loss of the main control tower, thankfully there was only one fatality recorded at the airport. Heroic action taken by airport employees resulted in temporary communications being restored almost immediately and all incoming aircraft were safely diverted elsewhere. With no working lights, landings that night were prohibited; however, the airport was back in operation the next day during daylight hours only.

Portable radios were set up in the Lake Hood Tower, and traffic to both Lake Hood and the Anchorage International Airport were controlled by Lake Hood for the next year until a temporary replacement tower for the main airport came on line. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) shipped a prefabricated control tower to Anchorage. It was positioned east of Concourse A and used until the current tower and radar facility was constructed and opened for operation in 1977.

Elmendorf AFB also received damage. Their tower was in shambles and a portable tower was erected and used until a new tower was constructed. Elmendorf was able to continue their flight operations because of minimal damage to their runway and taxiway and Merrill Field, fortunately, didn’t experience any damage to either their ground surfaces or any critical structures.

For the next decade, Alaska experienced a tremendous earthquake-reconstruction period with numerous government agencies stepping in to help. President Johnson created the Federal Reconstruction and Development Planning Commission for Alaska.The Small Business Administration loaned millions of dollars to rebuilt homes and businesses.

Anchorage International didn’t let the earthquake stop its growth. In fact, just the opposite happened during the next few years. New concourses and a larger modern terminal were built, ticket areas and baggage claim areas were expanded and the South Terminal was created. By 1970, the airport began planning for the arrival of the Supersonic Transport (SST) aircraft by constructing another East/West runway parallel to the existing runway.

In January and February of 1974, the first SST – the Concorde 201 arrived in Alaska for cold weather testing. During one of its overnight flights to Anchorage, I had the unique opportunity of being able to board and explore this marvelous aircraft. What British Airways and Air France created and planned for – the fastest transoceanic travel in history – unfortunately, became a short-lived venture and on April 10, 2003, both airlines announced that they would retire the Concorde, primarily due to the poor economics of maintaining and operating this aircraft and the slump in air travel following the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States.

Although the anticipated business boom associated with the SST didn’t last, Anchorage and the AIA, by this time, were very well positioned for major economic growth, following the discovery of oil on the North Slope of Alaska and the construction of the Trans Alaska Pipeline System. The oil industry brought thousands of new residents and workers to Alaska plus millions of dollars of cargo associated with the pipeline and AIA was the central clearing station for most of these people and the cargo flights

Fortuitously, construction on the new AIA Control Tower and Radar Facility was completed and opened for business in 1977. At the same time, the Lake Hood Tower was decommissioned and its traffic is now controlled from the new tower at the International Airport.

The 1980s began a time of unprecedented prosperity in Alaska and for Anchorage, thanks to the millions and millions of dollars flowing into the economy from oil royalties. A new North terminal was built, which is known today as the North International Terminal and international passenger traffic steadily increased as many international carriers used Anchorage as a preferred route for international travel.

Until the late 1980s, Chinese and Russian airspace were off-limits.

Later in the decade, as Russian airspace opened to allow for alternative transoceanic routes, and as larger, long-rage jets came on line, international traffic decreased at AIA. Charter passenger aircraft continue to stop in Anchorage on seasonal international flights, but the scheduled passenger traffic is limited. The military also uses this terminal for some of its flights.

The 1990s saw numerous expansion projects and economic growth at AIA and although scheduled international passenger traffic had dropped off, other sectors were flourishing. Probably one of the most dynamic expansions involved that of air cargo and the incredible growth in this segment. The U. S. Postal Service, Fed Ex and UPS located their cargo distribution and sorting operations in Anchorage and many other international cargo carriers use AIA as their stop-over of choice. In 2013, AIA was the fifth-busiest cargo airport in the world, according to the Airports Council International. Nearly 2.5 million metric tons of freight landed at the airport recently and domestically, AIA was the second busiest cargo hub in the United States, second only behind Memphis International, FedEx’s homeport.

In 2000, the name of the AIA was officially renamed the Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport (TSAIA )in honor of the long-time service of Alaska’s senior U.S. Senator.

Major expansion and upgrades occurred all through the decade of 2000-2010, with main runway reconstruction and the construction of new taxiways. Other construction included the expansion and upgrades to C Concourse, a new Field Maintenance Facility, the new Anchorage Rental Car Center, major renovations to B Concourse and the South Terminal Seismic and Security Retrofit Project.

Today, TSAIA is a vital contributor to Anchorage and Alaska’s economy and is a critical link between Alaska communities, “the Lower 48,” Hawaii and international destinations. One in 10 jobs in Anchorage is directly or indirectly related to the airport, according to the 2015 Anchorage Economic Development Corporation’s economic study on the airport. They further report that $8 out of every $10 the airport spends on purchases from the private sector goes to businesses in Anchorage; airport infrastructure construction projects generate millions in earning for Anchorage companies; businesses located at the airport contribute at least $2.3 million in property taxes to the Municipality of Anchorage; and 71% of all Asia-bound cargo from the United States and 82% of all U.S.-bound cargo from Asia transit through TSAIA. Passenger flights make over 50,000 landings annually at TSAIA and cargo flights make over 86,000 landings. Annual passenger traffic hovers around the five million mark and is remaining fairly steady.

From humble beginnings sixty-five years ago to the key economic engine it is today, the Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport is of crucial importance, not only to Anchorage but to all of Alaska.

Lake Hood Seaplane Base

Major players in Anchorage’s aviation history are two small lakes located about four miles west of downtown Anchorage – Lake Hood and Lake Spenard. While seaplane activity started on Lake Hood about 90 years ago, Lake Spenard was developed as a recreational lake with swimming and picnic areas. A road was built to these lakes to provide access. As the seaplane traffic grew, it became apparent that there was need for more support facilities for this traffic and in 1938, a channel connecting the two lakes was opened up and a 2,200-foot gravel strip was built along the south side of the Lake.

As Alaska’s population grew, so did the desire to travel to remote areas of Alaska and the seaplane turned out to be one of the most popular methods of exploring Alaska, particularly since there are so few roads, even today, connecting so much of the land. General aviation has been and is at the heart of settlement and growth in remote areas of Alaska and is a key part of our State’s aviation history.

In the 1950s, the combined lakes, now known as the Lake Hood Seaplane Base (LHSB), were further developed when the seaplane base was enlarged and additional parking areas constructed. In 1954, an air traffic control tower was built and it continued in operation until 1977 when it was decommissioned and traffic control was turned over to the new tower at Anchorage International Airport.

Since Lake Hood was already established, with a road to it, and some infrastructure in place, when the City of Anchorage was looking for a good location for an expanded international airport, it was a natural choice to locate the new airport on the undeveloped land next to the Lake Hood facility. This was a good decision; thankfully, when the earthquake occurred in 1964, and the control tower at the Anchorage airport collapsed, traffic was still able to continue via the tower control from Lake Hood.

The 1970s brought significant changes to Lake Hood. In 1972, the airstrip on the south side of Lake Spenard was closed and a new 2,200-foot north-south gravel strip was constructed on the north side of the Lake. In 1975, and East/West channel between Lake Hood and Lake Spenard was dredged just north of the original channel. This channel was developed to provide a safe, slow-speed taxi-way between the two lakes. Five float plane tie-down channels were also constructed. Soon after this expansion, the beach at Lake Spenard was closed to swimming – too dangerous with all the planes constantly coming and going on the Lake.

Today, Lake Hood Seaplane Base includes a 4,540-foot by 188-foot East/West waterway and a 1,370-foot by 150-foot Northwest/Southeast waterway. It has 500 slips for floatplanes and 500 tie-downs at the gravel strip. In addition, several areas are designated as ski-plane parking areas.LHSB is the undisputed busiest seaplane base in the world.

LHSB has had a huge impact on the economy of Anchorage. According to a recent study by the McDowell Group, activity related to the Lake Hood Base is estimated at about $42 million annually. This includes the various service vendors, employment and labor income. A large number of fishing, hunting and wildlife viewing lodges are either entirely or partially dependent on flight service from Lake Hood. LHSB serves the majority of non-resident visitors who purchase flight-seeing tours during their visits to Anchorage. The Base also supports resource development throughout the State as exploration, development and research activities are supported out of this location.

A number of government agencies conduct business at Lake Hood, including the Alaska Department of Transportation’s Central Region headquarters, the U. S. Department of Interior’s office of Aviation Services, the Alaska State Troopers, the U.S. Air Force Civil Air Patrol and the Federal Aviation Administration.

A parking slip at LHSB is a coveted acquisition. Slip registration has a huge waiting list and many hopeful pilots wait years for a slip to be approved.

As construction on the TSAIA and LHSB occurred, one of the hidden benefits to the people of Anchorage was the establishment of a delightful walking path along the lakes. A person can walk around the lakes, watch planes take off and land, view the birds along the shore, stop for a picnic and enjoy this very unique and interesting Anchorage attraction.

Alaska Aviation Museum

In 1988, a group of Anchorage folks got together and established the Alaska Aviation Museum on the south shore of Lake Hood. Starting out in a simple two-story building, the Museum continues to expand and improve. Today it is comprised of three large exhibit hangars, a gift shop, a community-use center, small theaters for watching movies of Alaska’s aviation history, a large fabric-covered hangar used to protect historic aircraft, a fully-operational restoration hangar and a completely renovated old Merrill Field Tower Cab that is used to provide residents and visitors a great opportunity to view the life and traffic on Lake Hood and listen to the actual conversations from the air traffic control tower.

As important as Merrill Field and the TSAIA are to Anchorage, so is the LHSB. All of these various aviation venues, whether for general aviation, flights connecting the communities of Alaska or international traffic and trade, make up the fabric of life in Anchorage and are key factors in Anchorage’s economic health and growth.

Kulis Air National Guard Base

Kulis Air National Guard Base was a National Guard of the United States facility located adjacent to and on the south side of TSAIA and was home to the 176th Wing of the Alaska Air National Guard until that unit was moved to Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson (JBER) in February 2011. Utilizing the runway facilities of the new Anchorage International Airport, the Base opened in 1955 with the 144th Fighter-Bomber Squadron. Kulis had been home to the 176th Wing for more than 55 years and was the headquarters for many Alaskan rescue and recovery missions as well as international deployments.

The Alaska Air National Guard was formed in Anchorage in July 1952 when the Alaska Air Division Commander Maj. Gen. Ricks announced that the territorial government of Alaska was willing to invest $1.5 million to establish an Air National Guard unit in Anchorage, at the city’s international airport.

Kulis served as a major center for the coordination of disaster relief following the 1964 Good Friday earthquake. Guard members quickly converted a base warehouse into a shelter for citizens left homeless by the quake with a makeshift dining hall and more than 100 beds.

A few years later, the Kulis Base once again went into rescue mode after the disastrous Chena River flood in Fairbanks in 1967. Within hours of the first call for assistance, C-123 flights began ferrying disaster relief supplies to Fairbanks and evacuating residents to Anchorage. For two weeks following the call for help, Kulis would fly 138 sorties with its C-123s and C-54 Skymaster transport, carrying 2,371 people and more than 300,000 pounds of supplies.

In 1969, the 144th Tactical Airlift Squadron was authorized to expand to a group level and the 176th Tactical Airlift Group was established by the National Guard Bureau. The 176th Wing is the largest unit of the Alaska Air National guard. It is a composite wing with multiple missions, including global airlift, air-sea rescue, tactical airlift and NORAD air defense.

Kulis received a major upgrade in 1977, with the construction of a new maintenance building, an aerospace ground equipment support building and a new petroleum operations facility on base.

In 1990 Kulis became host to an additional squadron, as the 176th Wing added the 210th Rescue Squadron. But, in 2005,the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Commission listed Kulis as one of its bases recommended for closure and in 2011, the 176th Wing vacated Kulis for new quarters at JBER).

The 127 acres that formerly comprised Kulis has been turned over to the State of Alaska and TSAIA. The State is now actively seeking buyers and leaseholders to fill the property. Only the hangars, warehouse and other buildings are up for sale/lease – the State will retain ownership of the land.

100 Years – Aviation in Anchorage is a Major Part of All of Our Lives

We used to have a saying in Alaska that more people had pilot’s license than driver’s licenses. That may not be true today, but certainly a large percentage of folks in Alaska have their own airplanes and use them for a wide variety of reasons – whether for sightseeing, fishing on remote streams, hunting in non-populated wilderness, bringing equipment out to a mining camp, showing Alaska off to a visitor or enjoying any of the many activities that makes up the fabric of life in Alaska.

Anchorage is not much different than elsewhere in Alaska. In addition to the five major controlled airports in the Anchorage area, we are also fortunate to have many smaller and non-controlled airports, airstrips and waterways. On any given day, in any season of the year, you will find aviation activity at the Birchwood Airport, Girdwood Airport, Bold Airport on Eklutna Lake, the Campbell Airstrip, the Goose Bay Airstrip and Campbell Lake Seaplane Base, just to name a few. Go either north or south just a few miles and you can land at many other facilities, such as the Palmer Airport, the Talkeetna Airport, the Willow Airport, the Seward Airport, the Kenai Airport, the Soldotna Airport, the Ninilchik Airport, the Iliamna Airport, the Homer Airport or the landing fields at Seldovia, Port Graham, Nanwalek, Beluga or Tyonek.

Alaskans love to fly. Whether we live in the city or in the rural areas of Alaska, we all depend upon the airplane. In Anchorage we are especially blessed to have so many options when choosing a certified air carrier or a well-maintained support facility.

About the Author

A life-long Alaskan with ties to Rural Alaska, the Interior and Southcentral, Gail Phillips has long been involved in local and state government, private enterprise and public policy. She served 10 years in the Alaska House of Representatives, including four years as Speaker of the House. Her professional resume includes teaching, private businesses and placer mining. Gail has dedicated much of her life to helping to formulate effective public policy regarding the wise use and protection of Alaska’s resources. She and her husband Walt live in Anchorage. They have two grown daughters.

RESOURCES

On-line articles from WIKIPEDIA

“Delany Park Strip” – Park History

“Elmendorf Air Force Base History”

“Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport”

“Lake Hood Seaplane Base”

“Kulis Air National Guard Base”

“Alaska Air National Guard”

“Airports of Alaska”

Municipality of Anchorage

“Merrill Field – Anchorage Aviation History & Development”

“Merrill Field – History of Russell Merrill”

Municipal documents regarding establishment of Merrill Field

Alaska Journal of Commerce

“Anchorage & Aviation: Flying Through Time” by Elwood Brehmer, June 3, 2015

E-mail communication with Elwood Brehmer, January 2016

U.S. Air Force – Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson

Fact Sheet: “Elmendorf Air Force Base History”

Airport Guides – U.S. Airports

“Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport (ANC) – History, Facts & Overview”

(Anchorage, Alaska – AK, USA)

Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities

“Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport – History”

Anchorage Economic Development Corporation

“Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport” – 9/14, Amended January 2015

“AIAS Air Cargo Related Economic Development Opportunity Assessment” 9/14

“Lake Hood Seaplane Base Economic Impact Study” 9/14

“TSAIA Economic Impact Report” 9/14

Alaska Dispatch News

“Lake Hood Seaplane Base – the Center of Anchorage General Aviation”

By Rob Stapleton October 14, 2010

“Vacated Anchorage Guard Base is Open to a New Future”

By Lisa Demer July 17, 2011

The McDowell Group

“Economic Benefits of Lake Hood Seaplane Base” September 2013

Alaska.org

“Lake Hood Floatplane Base Walking Tour” – Lake Hood History